I’D SWIPE RIGHT ON YR METADATA

by Liat Berdugo

Even as metadata I want to

feel your body beside me

congregate with other metadata

know what it is to be knownbiblically

-Martin Rock, Residuum

<><><><>

Questions of identity and personhood take on many dimensions, but perhaps flare -- existentially -- at times of mating. When you get close to another, where is it that you end and someone else begins?

A year ago, most of my studiomates were on Tinder. We were swiping left and right, right and wrong, until one of us -- call him S -- found a match. One day S and his match accidentally compared Amazon suggested products lists. S’s list was full of boat pumps and high-visibility neon swag. “Oh, I’d swipe right on that,” said S’s new love. Back in the studio we dreamed of a dating app based off a user’s metadata, not their photos. How utterly transparent it would be, this confluence of capitalism, algorithmic intelligence, and true materialism! This, this would be metadating.

Thus the unquantifiable, distributed, imperceptible self rears its head: with all your metadata flowing freely about the Internet -- bought and sold as hot commodities that make you absorb more debt in the neoliberal economy -- where is it that your metadata ends and mine begins?

<><><><>

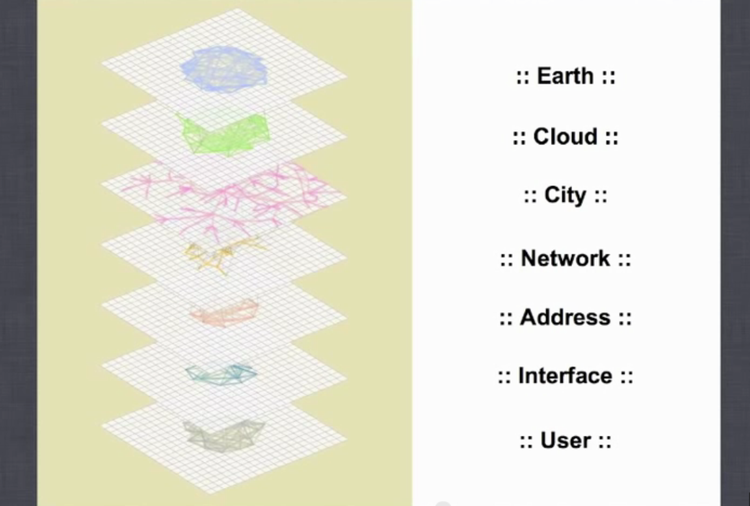

In February of this year, Benjamin Bratton published his long-awaited book, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (MIT Press, 2016). In it Bratton proposes a seven-layered system of computation that comes together as a megastructure -- an ecosystem of governance, called “the Stack.”

Benjamin Bratton, The Stack.

The imperceptible self I speak of is, at its core, concerned with the level of Bratton’s “User” -- not networks, not cities, not addresses nor interfaces. And, this imperceptibility concerns itself with a key paradox of the User’s position: he suffers from, as Bratton writes, the “contradictory impulse directed simultaneously toward his artificial over-individuation and his ultimate pluralization, with both participating differently in the geopolitics of transparency.”˚ The movement towards the quantified self is rife with this contradiction. At first a user is highly individuated, flooded with data about his step count, his heartbeat, his caloric intake. But then, as data that is “not him” is added to the system -- information about the biome more broadly, about environmental history, about genetic history and genetic futures -- the quality of the “self” as contained within an individuated and well-delineated body recedes, leaving in its wake the existential lesson that a User is only at the confluence of many planes of systems and data points. The subjecthood of the user is at first overproduced, and then exploded -- like a balloon pumped too full of air.

When the subjecthood of the User is exploded, what remains is the imperceptible self. We are left with a self unquantified, a self obfuscated. We are left with egoless identity where subjecthood lies in decay. We are left with many things to scratch out -- as poet Martin Rock writes, “Even as metadata I want to feel your body beside me // congregate with other metadata // know what it is to be known biblically” -- and we are left with many things to still desire. Even our metadata wants to be wanted.

<><><><>

Or, perhaps, our metadata is wanted too badly already.

In these moments, when my my metadata flows too freely, I think of my favorite champion for the Unquantified Self movement, Unfit Bits -- a work by artists Tega Brain and Surya Mattu. Unfit Bits is a set of physical systems for fitness tracking devices that personify the self and produce personal data “as if” a User had moved, jogged, or stepped. Brain and Mattu employ commonplace objects -- metronomes, bicycle wheels, drills -- to simulate human movement in humorous, low-fidelity ways. As insurance companies offer discounts to customers who not only agree to be tracked and quantified, but also whose data puts their fitness above thresholds for acceptable activity, Unfit Bits spoofs and distributes the self.

Brain and Mattu frame their work in terms of freedom -- proclaiming “Free your fitness. Free yourself.” But I see this work as a step towards freedom gained by a death of the User as we know him. In Unfit Bits, the new User is the metronome, the drill -- in other words, the machine. As the sovereignty of the subject dies, this death makes room for a proliferation of Users of different, non-human sorts -- Users can be dogs, wheels, high frequency trading algorithms, or something else all together.

˚ Bratton, Benjamin. “The Black Stack.” e-flux Journal #53 (2014): n. Pag. Web. 2 June 2016.

Tega Brain and Surya Mattu, Unfit Bits: The Metronome.

Tega Brain and Surya Mattu, Unfit Bits: The Drill.

Tega Brain and Surya Mattu, excerpt from Unfit Bits: The Guide.

Obfuscation -- the “deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusion, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance and data collection”˚˚, as media scholar Helen Nissenbaum describes it -- is key to Brain and Mattu’s practice. The imperceptible self can make choices to remain more imperceptible by obfuscating his metadata. Such is the work of Howe, Nissenbaum, and Zer Aviv’s AdNauseum, an omnivorous browser extension that clicks every ad served a User as he browses the web, thus polluting the User’s online profile. This obfuscation is different than camouflage: it acts by flooding the algorithmic system (another User!) with false bait. AdNauseum makes it look like the User swipes right on any ad they’ve ever seen on the Internet.

˚˚ Bruton, Finn and Nissenbaum, Helen. Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Invisible.

AdNauseum, of course, lives in the larger world of obfuscation alongside BioArt projects such as Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Invisible, a tactical kit for protection against new forms of biological surveillance. And none of this is new: my favorite example of obfuscation in media dates to Kubrick's 1960 film, Spartacus. In its most famous scene, the recaptured slaves are told they must identify and give over Spartacus in exchange for their freedom; instead, each slave proclaims “I’m Spartacus.” Spartacus himself is obfuscated -- his subjecthood decayed for his own safety and for the unity of the masses.

What I love about obfuscation is its close relation to subjecthood-in-decay. With obfuscation, the self becomes a loosely gathered moving target -- of metadata, of impulses and intentions, of men shouting “I’m Spartacus”. This moving target sits behind the thin veil of stability (the skin of the User’s body, the single-sign-on Username). Sometimes, the difficulty of maintaining this veil of a stable self-image in the face of what scholar Lauren Berlant calls a “threat of dissolution by the fragile infrastructures for maintaining fantasy” becomes all too apparent -- as best exemplified by the combover subject˚˚˚. Berlant writes:

The subject of the combover stands in front of the mirror just so, to appear as a person with a full head (of hair/ideas of the world). Harsh lighting, back views, nothing inconvenient is bearable in order for the put-together headshot to appear. No one else can be fully in the room, there can be no active relationality: if someone else, or an audience, is there, everyone huddles under the open secret that protects the combover subject from being exposed socially confronting the knowledge that the world can see the seams, the lacks, and the pathos of desire, effort, and failure.˚˚˚˚

The combover identity, then, is this thin veil: a combover is what a User fabricates in the morning with what’s left of his hair; a combover only fools others from one vantage point, only with correct lighting, only without careful looking. A subject who puts on the combover identity wants to maintain a semblance of youth -- and perhaps even of sexual allure. The combover subject wants to “know what it is to be known biblically,” just as Martin Rocks metadata want.

˚˚˚Berlant, Lauren. “Combover (Approach 2).” Web blog post. Supervalent Thought. 19 December 2010. 2 June 2016.

˚˚˚˚ Ibid

Donald Trump’s combover blown over, source unknown.

<><><><>

So what is it about being together? What is it to be known? What is to be known biblically?

Perhaps the apex of being known, as a User, is fully giving over you data privacy -- not as an act of banking or hacking, but as an act of perfect entanglement -- of love, even. Here I think of artist Brian House’s, Tanglr, a browser extension that anonymously links you with another person. When you browse the web, your partner is taken to the same URLs. Likewise, when your partner browses, your browser changes to what they're seeing. The two of you have to work it out together, as a loosely-knotted coupling that stumbles through the Internet. The two of you have to work it out together, amassing each other's metadata along the way. Again, Martin Rock: “Even as metadata I want to… congregate with other metadata.” Perhaps this is the truth of relationships: the more you stay together, the more your metadata begins to resemble one another’s.

Brian House, Tanglr.

<><><><><>

So where is it that you end and some else begins? Or to push this question further -- how might you use the Internet to scavenge for your own identity?

These are the questions I’ve been asking recently with my own collaborative artistic practice under the name Anxious to Make. Together with artist Emily Martinez, I’ve been commissioning sets of fake twins on sharing economy sites (like Fiverr.com) to act as if they were me. I give them scripts, I try on roles. Thus I slowly piecemeal my identity together -- I scavenge for it: I am a blonde skinny woman from LA; I am a middle aged Indian man; I am an Australian teenage boy. I use the accelerationist, neoliberal economic landscape of Internet-spokesmen-for hire to simultaneously explore the current state of the so-called “sharing economy”, and also to explore roles outside my own personal comfort zone. For a moment, I believes in absurdist extremes as way to examine these contemporary realities.

What happens when the collapsing distances between us is interrogated? Are you the sum of your step count, your browser history, your online shopping cart? Are you dispersed on the internet, in exile? Or are you localized in an entropic influx of worms, feelings, and anxiety? Are you simply a collection of your metadata?

I propose that this is the self, imperceptible: it is a world where I’d swipe right on your metadata. It is a world where “even as metadata I want to feel your body beside me,” (Rock), where even your metadata will one day look at itself in the mirror, and think to itself: I’m getting older, time for a combover.

References:

Berlant, Lauren. “Combover (Approach 2).” Web blog post. Supervalent Thought. 19 December 2010. 2 June 2016.

Bratton, Benjamin. “The Black Stack.” e-flux Journal #53 (2014): n. Pag. Web. 2 June 2016.

Bratton, Benjamin. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016.

Bruton, Finn and Nissenbaum, Helen. Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015.

Rock, Martin. Residuum. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2016.

About the Contributor: Liat Berdugo is an artist, writer and curator whose work creates an expanded and thoughtful consideration for digital culture. This essay was originally conceived of as an exhibition precis in joint partnership with Tiare Ribeaux